Congratulations to Sarah Whiteley on publication by the journal EvoDevo of her honours work. In this paper she not only characterizes in great detail the embryonic development of the dragon but shows that sex reversal does not interfere with body or genital development in a way that might compromise viability.

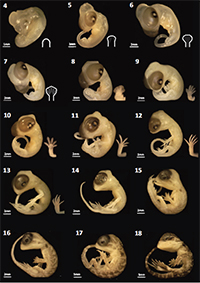

This meticulous work is central to progress on the latest activities of Team Pogona, where exploring gene expression and methylation requires precise estimation of the stage of development in the embryo. Sarah was awarded a first class honours for her thesis on the topic, by Queensland University where she worked under the supervision of Vera Weisbecker and Clare Holleley.

Development of male or female-specific phenotypes in squamates is typically either controlled by temperature-dependent sex determination (TSD) or sex chromosomes (GSD). However, while sex determination is a major switch in individual phenotypic development, we know little of the interplay of evolutionary transitions between GSD and TSD and the evolution of phenotype more generally, particularly the fast-evolving and diverse genitalia.

In this paper, Sarah and her colleagues capitalise on a unique opportunity to examine the impact of sex reversal on the embryological development of the central bearded dragon (Pogona vitticeps). This opportunity arises because genetically male individuals (ZZ chromosomes) reverse sex at high incubation temperatures. This can trigger the evolutionary transition from GSD to TSD in a single generation, making the dragon an ideal model organism to examine the consequences of such transitions on embryology.

Sarah provides the first detailed staging system for the species, with a focus on genital and limb development. Apart from faster growth in 36°C sex-reversing treatments, body and external genital development were unperturbed by temperature, sex reversal, or maternal sexual genotype. A surprising result was that all females developed hemipenes similar to the males, but they regress close to hatching in the females.

The tight correlation between embryo age and embryo stage allows the precise targeting of specific developmental periods at different temperature treatments, so important in our transcritpomics and methylomics work on this species. The stability of genital development in all treatments suggests to Sarah that the two sex determining mechanisms have little impact on genital evolution, despite their known role in triggering genital development.

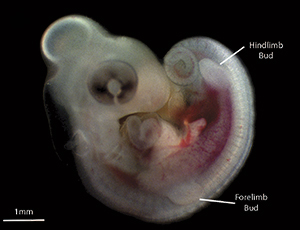

Sarah was also able to better characterise the embryonic stage of the dragon at the time of egglaying. Unlike turtles, some lizards and snakes develop quite a ways while still in the mother's oviducts, before the eggs are laid. For Pogona, the little embryo at time of egglaying is shown in this video.

With one paper under her belt, Sarah is preparing a second from her honours using gonad histology and scanning electron microscopy to reveal more weird aspects of dragon sexual development.

Read more in the press release issued by the University of Queensland, or in the EvoDevo paper itself: Whiteley, S.L., Holleley, C.E., Ruscoe, W., Castelli, M., Whitehead, D., Lei, J., Georges, A. and Weisbecker, V. 2017. Sex determination mode does not affect body or genital development of the central bearded dragon (Pogona vitticeps). EvoDevo 8:25. It is open source.